How to Write with Style

In what follows, I present five rules to follow if you want to write in a clear style. These rules are for writing philosophical papers but they also apply to non-philosophical subject matters as well (e.g., argumentative writing more generally). I provide arguments for these rules. Since I don’t think any of these arguments are knockdown arguments, I’ll present some criticisms to these rules.

Rule 1: Avoid jargon and five-dollar words

Before we formulate this rule more precisely, let’s provide some informal definitions. “Jargon” refers to the technical terminology of a field of research, a profession, or special activity. Jargon tends to be difficult to understand by those not working in that special activity. For example, the term “supervaluation” is a piece of jargon used by logicians. Or, the term “gank” is a piece of jargon used by those that play the online video game League of Legends.

Consider the following quote attributed to Mark Twain:

Don’t use a five dollar word when a fifty cent word will do.

To understand this quote, let’s define the meaning of a “fifty-cent word” and a “five-dollar word”:

- fifty-cent word: a short, simple, or frequently used word

- five-dollar word: a long, complex, or uncommon (perhaps archaic) word (often perceived (by some) as being sophisticated or scholarly).

Some examples of five-dollar words and their roughly equivalent fifty-cent versions:

| Five-dollar word | Fifty-cent version |

|---|---|

| perspicacious | insightful |

| extemporize | improvise |

| coquettish | flirtatious |

| suffuse | spread |

| fastidious | detail-oriented |

| cromulent | acceptable |

| betwixt | between |

The meaning of the quote is now clear. If there is an fifty-cent word and a five-dollar word and the fifty-cent word works just as well for communicating your ideas, use the fifty-cent word instead.

Let’s formulate our rule of style:

Whenever possible, avoid jargon and five-dollar words in favor of shorter, simpler, and more common words.

Here is an argument in support of this rule:

- P1: One of the primary goals of writing is to communicate information as precisely as possible to your intended audience.

- P2: The use of jargon and five-dollar words over equivalent fifty-cent words limits the number of people within your audience who will receive this information.

- C: Therefore, whenever possible, you ought to avoid jargon and five-dollar words.

In response to this rule, I’ve been told that the expression of your ideas is more important than the communication of them to an audience. That when people write, they are writing for themselves. They are trying to get their thoughts onto the page and so the rule to restrict language in this way runs in conflict with creative expression.

Rule 2: Focus on your topic

Some people write about things that are not directly related to the primary topic. For example, suppose you are tasked with writing an essay about what an artwork says about time (its nature or our experience of it) and how it says it.

In the paper, you write about how fantastic the artwork is and how it has made an impression on millions of people across the globe. As your reader, I may agree with you, but this information is off topic: the task of the paper was to write about the artwork’s relation to time, not to evaluate its quality or its impression on people.

Rule 2: Whenever possible, avoid including information that is irrelevant to the central topic of your paper.

Here is an argument in support of this rule:

- P1: One of the primary goals of writing is to communicate relevant information as precisely and as quickly as possible to your intended audience.

- P2: Including irrelevant details in your writing takes time

- C: Therefore, only include information that is directly relevant to your topic.

In response to this rule, I’ve been told that these details often help engagement on a personal level. Writing is partly about self-expression.

Rule 3: Avoid anecdotes

Let’s consider another rule that could be a species of the previous rule. Suppose you are debunking arguments put forward by people who believe that the earth is flat (flat-earthers). In debunking these arguments, you offer a few stories about flat-earthers you’ve encountered. These stories are anecdotes. An anecdote is a short story involving a real event, experience, or person. Why are you offering up an anecdote?

First, you might offer an anecdote because it helps explain why you are interested in debunking the claims made by flat-earthers. If so, then, at least for one point in your writing, the debunking of the claims is not the subject matter. Rather, you are the subject matter. In some cases, your audience might not care about you or your motivation. They only want to know about the debunking. So, you are offering irrelevant information: violation of rule 2.

Second, you might offer an anecdote as evidence for a claim you are making. One way to do this is to tell a story about a person who you take to be representative of a position you plan to criticize. In this case, ask yourself whether anything about the person is relevant for criticizing the position itself. For example, suppose again you plan on debunking positions held by flat-earthers. To introduce the topic, you offer an anecdote of a flat-earther you met. You point out their straggly appearance, indicate the political party they support, and describe some of their mannerisms. None of this is relevant to the debunking of the position.

It is my contention that, except in rare cases involving people who live extraordinary lives, adding anecdotes into one’s writing should be avoided. They tend to be irrelevant, prompt readers to engage in fallacious forms of reasoning, and a waste of your reader’s time.

- P1: One of the primary goals of writing is to communicate information that is relevant and rationally supported, and to do so as precisely and as quickly as possible to your intended audience.

- P2: Anecdotes tend to introduce irrelevant information.

- C: Therefore, avoid anecdotes.

In response to this rule, some people are highly impressed by personal anecdotes and so their use has persuasive value. If your concern is impressing your audience rather than rationally persuading them, then anecdotes can be a powerful tool.

Rule 4: Avoid sweeping generalizations (even if true)

Suppose you have just read a very short paper that has argued that “knowledge” should not be understood as “justified true belief”. You will to develop this idea and so wish to use point to a few samples of philosophers who understand do understand “knowledge” in this way. Your plan, of course, is to show how they are mistaken. However, suppose you begin my paper as follows:

From the dawn of time, philosophers have consider what it means to know something.

There are a few things wrong with starting your paper in this way. First, you do not plan on writing a history of how philosophers have understood the meaning of “knowledge”. So, this sentence is off topic (see Rule 2). Second, this particular generalization is controversial (and likely false).

If we should avoid generalizing, what is a better way to start? My suggestion is that you restrict your claims to (1) generalizations that you have a high degree of confidence that others would accept or (2) what you can prove (or will prove in your paper). Here is a suggestion:

In this paper, I provide evidence that some philosophers have analyzed “knowledge” as “justified, true belief. I argue that this analysis is mistaken.

Notice that rather than making a sweeping generalization over the history of time and philosophy, the above statement is restricted to what some philosophers think about knowledge. To prove this, you will provide examples in your paper.

Here is an argument in support of this rule:

- P1: One of the primary goals of writing is to communicate information that is relevant and rationally supported, and to do so as precisely and as quickly as possible to your intended audience.

- P2: Sweeping generalizations in your work tend not to be directly relevant to your paper topic and are usually not supported by evidence or argument.

- C: Therefore, avoid sweeping generalizations.

In response to this rule, I’ve been told that false generalizations encourages engagement. A provocative generalization challenges the reader to find counter-examples.

Rule 5: Use Examples and Illustrations to Aid Understanding

There is the famous saying (attributed to Confucius, Arthur Brisbane, and Fred R. Barnard, and others) that “a picture is worth a thousand words”.

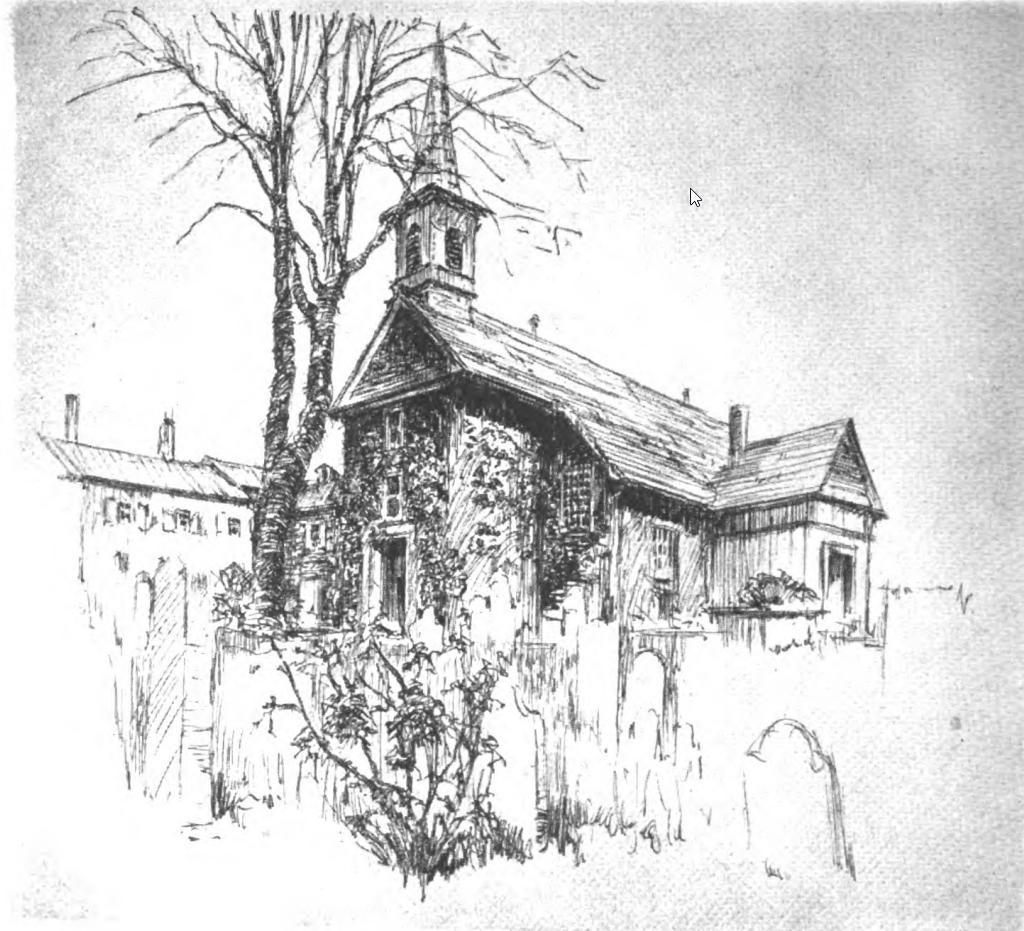

It is hard to know what “worth” means here. It does seem that pictures and examples can be more “economical”. For example, consider the following remark about etchings:

“A capable etcher holds within a few black lines the interpretation of a romance and feeling impossible to tell in a thousand words or a dozen colors.” (From Printers’ Ink Monthly, Vol. 1, No. 10, Sept. 1920)

Whether pictures / examples are better or economical or not, they do tend to (1) aid in understanding complex topics and (2) be memorable or attractive.

Here is an argument in support of the use of examples:

- P1: One of the primary goals of writing is to communicate information that is relevant and rationally supported, and to do so as precisely and as quickly as possible to your intended audience.

- P2: Pictures, diagrams, and examples aid in understanding of complex (abstract) topics.

- C: Therefore, use plenty of pictures, diagrams, and examples.

In response to this rule, there is the claim that pictures and examples can mislead readers since they often oversimplify and are not as informative as written text. For example, compare various attempts to reproduce the shield of Achilles and compare it against Homer’s description of it in The Illiad (Bk XVIII):

Rule 6: Avoid Rhetorical Questions

A “rhetorical question” is a sentence that takes the form of a question but is used for a reason other than soliciting an answer. Let’s consider two examples.

First, rhetorical questions can be used to insult people. Suppose Liz asks Tek the following: “are you stupid?” Liz is not asking Tek whether he is stupid nor is she expecting a “yes” or “no” answer to this question. Instead, Liz is asserting that Tek is stupid.

Second, rhetorical questions can be used to provoke thought or prompt discussion. Suppose Liz and Tek are the parents of Rob. Rob has a friend at school who only has a single parent. Liz says to Rob, “can you imagine what your life would be like without your father?” In this example, Liz is again not asking Rob whether it is possible for him to imagine life without Rob’s father. Instead, Liz is suggesting that Rob try to imagine what his life would be like without his father.

In general, the use of rhetorical questions should be avoided in academic writing. The reason for this is because it is an indirect form of expression. In the case where Liz asks Tek “are you stupid?”, she is using a sentence that has the form of a question to express the sentence “you are stupid.” A more direct way of expressing her view would be to utter the sentence “you are stupid.”