How to Clarify

Unclear language is said to die as soon as it is spoken since it fails to be understood by those that hear it.

Since many of our ideas (e.g., person, free will, beauty) are unclear, one goal of writing is to clarify the language we use. In clarifying an idea, we generally try to (1) make the idea more understandable or (2) make it more precise (or both).

Methods of Clarification

Practically speaking, how do we clarify an idea? There are several methods:

- Define the idea: Provide a definition of the idea.

- Reduce generality: choose a word with a narrower application

- Precisify

- Give an example: Provide an example of the idea.

- Compare and Contrast: Highlight how the idea differs from other relevant or closely related ideas.

- Disambiguate: Articulate the different senses of the term and distinguish between them.

- Highlight misconceptions: Identify and correct misconceptions or contentious beliefs people have about the idea.

Define the idea

Let’s consider each one of these. First, consider the concept of idea of “doubt”. In order to gain greater clarity concerning this idea, one thing we can do is to define it. One type of definition is a dictionary definition. Consulting the dictionary, we might find that doubt is defined as follows:

“a feeling of uncertainty or lack of conviction.”

Another way to define an idea is to provide what necessary and sufficient conditions need to be met in order to doubt something. That is, what is both required to doubt something and what is enough to doubt something. Here is an example:

A person doubts a proposition p if and only if they have a feeling of uncertainty about whether p is true.

Once a definition is supplied, further clarity can be gained by defining any unclear words in the definition itself. This is sometimes called “analysis” or “decomposition” (defining not only the idea itself but the ideas that compose the word). Here is an example:

There are three key ideas involved in the concept of doubt. First, doubt is a specific type of feeling (a psychological (emotional) state of a person). Second, doubt is characterized in terms of uncertainty (the lack of knowledge about something). Finally, when a person is in a state of doubt, they lack conviction (do not have a firmly held belief about that which they doubt).

Reduce Generality

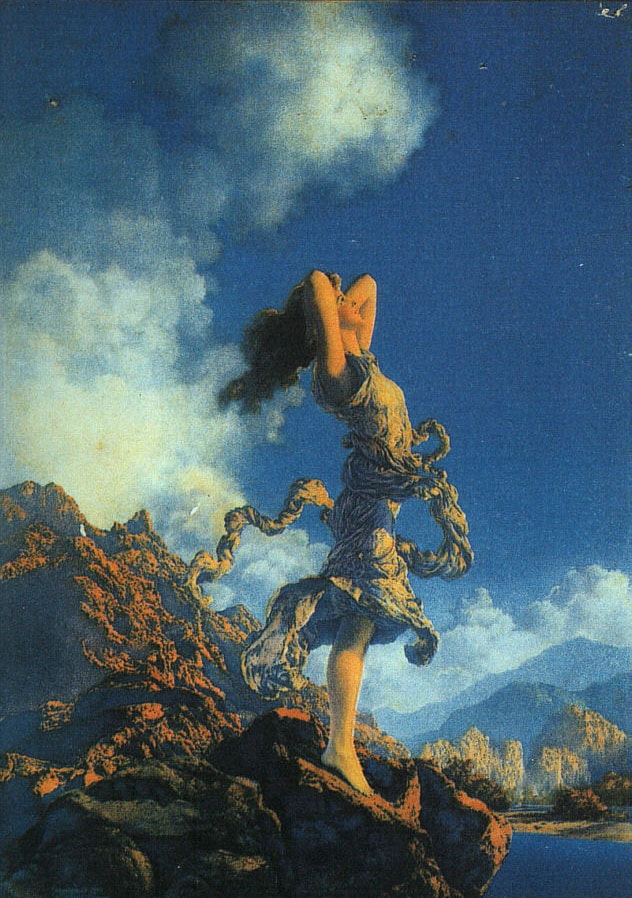

In some cases, we can make our writing more precise by being less general. We can achieve this by using words that have a narrower range of application. For example, suppose I am describing the artwork Ecstasy (1929) by American painter Maxfield Parrish.

I could say that Parrish uses a lot of blue in the painting. However, “blue” is a general term: it could refer to navy blue, royal blue, neon blue, etc. What I could say is that Parrish’s painting was a particular hue of blue (Cobalt blue or “Parrish blue”) that is more vibrant than other blues.

In the above example, more precision is gained by selecting a word or phrase whose application is narrower than the more general word, e.g., Parrish blue vs. blue. Such a feat often involves knowing various things about the what we are talking about, e.g., knowing that different hues exist.

Precisify

In some cases, our primary goal is not to articulate what people mean when they use the word. If that were the case, then a dictionary definition (along with analysis) would be sufficient. In addition, we cannot clarify our meaning via an increase of information or greater knowledge about what we mean or what we are talking about.

Instead, more precision can be gained by precisifying the idea. In precisifying an idea, the goal is to fix problems or confusions with the existing meaning of the term by (1) keeping the essential function or meaning of the term but (2) replacing unclear or confusing aspects of the term with precise ones. In essence, we are making our ideas or words more precise by adding something to that idea.

Here is how Quine defines explication:

“[When we explicate,] we do not claim synonymy. We do not claim to make clear and explicit what the users of the unclear expression had unconsciously in mind all along. We do not expose hidden meanings […]; we supply lacks. We fix on the particular functions of the unclear expression that make it worth troubling about, and then devise a substitute, clear and couched in terms to our liking, that fills those functions.” (Quine Word and Object: 258-9).

Here is another statement from Quine about explication:

“We have, to begin with, an expression or form of expression that is somehow troublesome. It behaves partly like a term but not enough so, or it is vague in ways that bother us, or it puts kinks in a theory or encourages one or another confusion. But also it serves certain purposes that are not to be abandoned. Then we find a way of accomplishing those same purposes through other channels, using other and less troublesome forms of expression. The old perplexities are resolved.” (Quine Word and Object: 260).

Let’s illustrate explication through what is sometimes called precisification (we’ll keep things non-technical). Consider that the vague term “tall” has unclear boundaries. While a 7’0 person is clearly tall and a 4’0 person is clearly not tall, the meaning and our use of the word “tall” does not pick out a precise cut-off height such that people who are that height are tall and people who are 1 inch shorter are not tall. This creates a problem for reasoning since “if a person 7’0 is tall, then a person 6’11 is also tall” (a small difference in height doesn’t make a big enough difference in terms of whether or not someone is tall or not). But, if that is the case, then “if a person 6’11 is tall, then a person 6’10 is also tall” and so on to the absurd conclusion that a 4’0 person is tall. Vague terms throw a wrench in how we reason. One simple way to solve this problem is to make the term “tall” precise by drawing a sharp boundary between the tall and non-tall. In doing this, we are precisifying tall and thus fixing the problem where we reason to the conclusion that a 4’0 person is tall (although we may admit new problems!).

Give an Example

One way to clarify an idea is by making it more precise. Another way is by making it more vivid and understandable. One way to do this is through pictures, diagrams, and examples.

You have probably heard the expression “a picture is worth a thousand words.” This is true for several reasons. First, pictures can be a more efficient way of communicating information than words. Suppose Tek wishes to tell Liz what his friend Jon looks like. He could describe Jon to her, but this would be a somewhat lengthy process. On the other hand, a picture of Jon almost instantly conveys his appearance.

Second, in some cases, it is easier to convey information through the use a picture. This can occur for several reasons but one of them is that sometimes we feel as though there are aspects of the situation or the object that we are describing that we (at least at this moment in time) cannot describe. This could be because the object is too complex or because we lack the descriptive skills to describe the object. Consider our earlier example where Tek is attempting to describe Jon to Liz. Tek may struggle to describe Jon’s eye color as follows:

“his eyes are blue but not blue blue. I guess there is some orangish yellow in them, or maybe it is orange and yellow. Like you know, it goes from orange to a lighter shade of orange. I suppose there are some white flecks scattered in the eyes. Now I guess I haven’t told you how all of this color is arranged. Most of the yellow-orange colors are toward the middle part of the eye. What’s that called? Oh yeah, the iris.”

Notice that the Tek struggles to describe the Jon’s eye color, which is a borderline case of hazel-blue and hazel-grey.

Here is another example. Suppose again I am describing the painting Ecstasy (1929) by American painter Maxfield Parrish (see this section for the image). I want to say that a particular hue of blue makes this painting vibrant. Of course, I could be more precise by describing the chemical formulation of Cobalt blue pigment (Al2CoO4), but I could make the claim that this blue creates vibrancy by giving examples of other artworks that are “vibrant” and that use the same hue, e.g., this 15th century Ming dynasty jar:

In some cases, we do not have pictures to rely upon. This is routinely the case when what we are trying to clarify is abstract or general. In such cases, it is useful to use descriptive examples to make the clarification of our abstract concepts more understandable.

For example, suppose that we wish to clarify what it means to “doubt” a proposition P. That is, we are trying to explain to someone what “doubt” means. One way to do this is to give examples where a person doubts P and where the person does not doubt P.

Suppose Liz doubts whether Tek is nice. If this is the case, then Liz has a feeling where she does not know whether Tek is nice and does not have a firm belief concerning whether Tek is nice.

Or, suppose we wished to make some concept of of free action more understandable. For example, suppose we wanted to point out that sometimes a person acts on their desires but the fact that their desires are determined by an outside force means that their action is not free. Here is an illustration:

Suppose Tek wants to eat a juicy cheeseburger. He buys the cheeseburger and eats it. While this appears to be a free action, let’s suppose that his desire to eat the burger is due to an evil demon who implanted in his mind the desire to eat the cheeseburger. In such a case, he would not be free.

Compare and Contrast

Another way to clarify an idea is to highlight how the idea differs from other relevant or closely-related ideas.

Suppose again I am describing the painting Ecstasy (1929) by American painter Maxfield Parrish (see this section). I could clarify Parrish blue by contrasting it against other blue hues.

Similarly, with the idea of doubt, I could contrast it against several related ideas as follows:

Doubt can be contrasted against belief or knowing. If a person believes a proposition, then they do not feel uncertain about that proposition. With respect to the feeling of conviction, a person in a state of doubt lacks conviction, but a person in a state of belief may or may not have conviction with respect to that belief.

In the above example, doubt is contrasted against the related ideas of belief and knowing. A closely-related idea to doubt is that of ignorance. Insofar as these are not the same idea, we can gain further clarity by distinguishing doubt from ignorance as follows:

Doubt is closely related to idea of ignorance, but these two notions are different in that doubt involves a specific type of feeling not required by ignorance. That is, when a person doubts a proposition, they feel uncertain. However, a person may be ignorant of something without feeling doubt about it. For example, if Liz is a computer programmer, she may have doubts about whether a program she has written will work. In contrast, Tek does not have any doubts about whether this program will work since he does not know of the program’s existence.

Disambiguate

Another way to clarifying an idea is to disambiguate the idea. To illustrate, let’s consider two different senses of the term “doubt”:

There are at least two different kinds of doubt. The first kind of doubt, we might call “emotional doubt”. This is where you feel uncertain about something but still act as though it is true. In contrast, there is emotional and active doubt. This is where you feel uncertain about something but act in a way that is consistent with your uncertainty about its truth. To illustrate, I may feel uncertain whether a glass floor in a large building will support my weight even though I have been assured by a team of engineers who are currently standing on the floor. If I nervously walk across the floor, I feel uncertain but I act in a way that is consistent with me believing it will support my weight. In this case, my doubt is theoretical.

Highlight misconceptions

It can also be helpful to highlight common misconceptions people about certain ideas (or aspects of the idea that are controversial). Specifying these misconceptions may be helpful since even after you have separated two different meanings of a term, people may backslide into treating the term in an ambiguous way.

A common example involves the use of the words “wrong” or “bad”. Some people talk as though what is legally bad (against the law) is the same as what is morally bad (evil). After you distinguish these two senses, people tend to accept that there are two different senses. However, they will later return to using them synonymously. Drawing attention to the fact that people incorrectly (or controversially) talk as though they believe “X is morally bad if and only illegal” may help to free them from this confusion.

Exercise

Pick any concept you want and clarify it using the strategies mentioned above. If you are struggling to think of a concept to clarify, try to clarify the following: game, country, sport, runner.